About

Presenting

Conference: SUR POLAR/Arte en Antartida

Buenos Aires, March 2008

Antarctic Animation:an overview

ABSTRACT

Antarctic landscape is beyond the experience of most of us, and to some it can seem terrifyingly remote. This remoteness and strangeness can get in the way of us getting to know it. But if we want to learn what the future holds for future generations it is important to find ways we can connect with this place. If animation is the visual language of change, can it be used to take us into the landscape to feel something of the changes measured and experienced by those who have worked there? Scientists use animations to visualise important data about landscape change. But these can sometimes be difficult for other people to read. As graphs, scientific visualisations can seem remote from human experience. Constructing and animating landscapes with the data, and with other Antarctic texts, we can visualise ourselves within this place. And when the changes we see happening appear like how we move, we can identify more easily with the data. Connecting to a moment experienced in Antarctica can bring us closer to knowing the changes that are happening there. With this as the premise, I am working with dancers, artists and musicians, responding to the texts of expeditioners exploring ways to animate their moments in the ice.

Conference: ANIMATED DIALOGUES

Melbourne, June 2007

Animating Antarctic Landscape:Dialogues in Art and Science

ABSTRACT

Animation can be used to reveal the Antarctic landscape through the various lenses of those who have observed and experienced it. It is important to understand the changes occurring in the Antarctic landscape itself, because they indicate global changes that impact on us all. To enliven our engagement with the physical landscape, it is insightful to observe its changes alongside the various aesthetic responses of those collecting the data. Written, spoken and visual texts provide evidence of landscape changes both scientifically observed, and aesthetically experienced. Analysis of these texts offers clues for animating the landscape and the gestural responses of the people experiencing it. Information sharing and collaborative interpretation are valued by Antarctic researchers. An online repository has been built to interconnect animated data and responses, and invite participation.

CHANGES OBSERVED IN THE ANTARCTIC LANDSCAPE

We hear about the decreasing sea ice extent around Antarctica, about its retreating glaciers, and diminishing wildlife. More and larger ice bergs, we are told, are calving from its ice shelves. We can only imagine what these changes look like, in terms of shape, scale, colour and motion. Still images are sometimes shown by way of illustration, yet rarely do we see the changes animated.

Data sets of changes observed in the Antarctic landscape are available from the archives of scientific organizations. Some are readily accessible on-line, yet their numeric and graphic formats can be difficult for a non-scientist to read. Animation is a way to capture these changes in a way that can be grasped for our visual understanding.

Figure 1a. Antarctic sea ice, through 1991

The longer wavelengths in the radar range of the electromagnetic spectrum have been used to penetrate the clouds and render images of the ice around Antarctica. Figure 1 is one of a series of these images available from the Gulf of Maine Aquarium website (On-line accessed, 2 July 2007), to animate a cycle (Figure 1a) showing the advance and retreat of ice around the continent throughout 1991.

Figure 1. Antarctic sea ice, November 1991

Figure 2. Antarctic sea ice, November 1978

Identifying images from this site was not straightforward. We hear that the ice extent is growing less. To animate the changing patterns in the cycle over years, more detailed information about the images is required. Enough source files from each month over many years need to be accessed to animate change.

The original satellite data was produced by the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado in cooperation with NOAA and NASA, and made available on-line by the US Geological Survey Global Change Research Program (On-line accessed, 2 July 2007). Figure 2 was eventually identified by its name, '7811s'. Familiarity with file naming conventions, and its location in a folder names '1978', suggested this image was taken on the 11th month of 1978. Further investigation of this site reveals incomplete sets of pictures available for each year they were taken. This imaging technology is relatively new, only beginning in 1978. so long term studies of changes with these are not possible. Comparing Figures 1 and 2, some changes in the distribution and thickness of ice in November in 1978 and 1991 can be speculated.

Animating a simple annual cycle is not the only way to show the changes in sea ice extent. Overlaying outlines of average maximum and minimum extents, for example, can reveal extremes.

AESTHETIC RESPONSES TO ANTARCTIC LANDSCAPE

Through analyzing the diaries and artworks of expeditioners, I find ways to draw, paint and animate their aesthetic responses to the Antarctic landscape. Preparation for this work involved observing the visual languages other artists have used to describe it.

Even for those who have worked in Antarctica for long periods, the landscape there remains a void, challenging the limits of our perception. It defies our expectations of framed foreground, middle ground and background. William Fox, who has a science background, explains these expectations from a biological perspective. He argues that we view through 'inherited templates' based on the cognitive wiring of our brains, evolved over millions of years inhabiting mountainous terrains with trees, rivers and lakes. (Fox, 2007;18)

Australian artists John Caldwell, Jan Senbergs and Bea Maddock were sent to Antarctica by the Australian government in 1987 as

...a major step towards bringing Antarctica into the Australian cultural experience.

(Boyer, 1988;11)

They were sent into alien territory to help familiarise the unfamiliar. As Peter Boyer wrote in their exhibition catalogue,

If works of art about Antarctica have a common element, it is probably a fascination for things vast, unknown and elemental.

(Boyer, 1988;1)

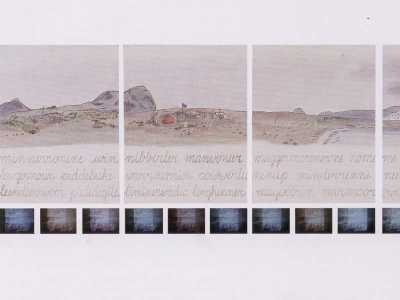

Figure 3 shows Bea Maddock's large, seven-paneled work, We live in the meanings we are able to discern (1988) supports that view.

Figure 3. We live in the meanings we are able to discern (detail), Maddock, 1988

Words fuse with imagery to stretch the eye across seven large panels depicting an expansive desert. The only evidence of human presence is a campsite. Antarctica had no indigenous humans, yet Maddock has written Aboriginal words in cursive script along the full length of the work, evoking the ancient knowledge of land long before Europeans so-called 'discovered' it.

After her return from Antarctica, Maddock produced Terra Spiritus, with a darker shade of pale (1993-98). This edition of prints was made to be displayed in a circle, mapping the entire Tasmanian coastline, as it would have appeared to an early explorer. Land features, with no hint of vegetation or buildings, are named in Aboriginal language in cursive writing, with their English names printed in small metal type beneath. By describing her home land as elementally as Antarctica, she suggests another way for us to see our own familiar place. Maddock's visual vocabulary involves lean pencil drawings made directly from life, repeating and evolving photographic images, and an integration of written and printed words and images. She was my teacher at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) in the 1970s, and I recognise her influence in the development of my own practice, particularly towards animation.

WRITTEN, VISUAL AND AURAL TEXTS OF EXPEDITIONERS

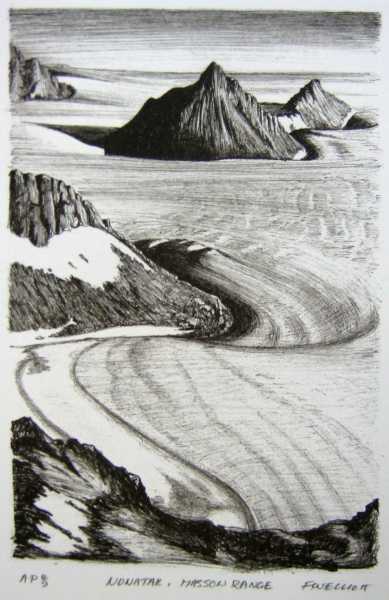

A range of written, visual and aural texts of Antarctic expeditioners have become available for study from a range of sources. Through a chance meeting at the Sydney Nolan Antarctic art exhibition in the Mornington Art Gallery in March 2007, I met Jack Ward. He worked at Mawson as a radio operator between 1955 and 1956. Reading his diary and hearing him describe his experiences provide material for animating his landscape perceptions. Fellow expeditioner Fred Elliott worked as a weather observer. Fred was also the official expedition photographer. His aesthetic response to the landscape was through photographs and drawings. Figure 4 is one of a collection of drawings he made in 1997, from photographs he took in 1956 of the mountain ranges behind Mawson.

Figure 4. Nunatak, Masson Range, Elliott, 1956

A potent and whimsical expression of how the Antarctic landscape can shape a man, is Man sculpted by Antarctica. Also known as Fred the Head, this large wooden head was made "to be sculpted by the elements to become a token of our humanity in an environment that we have only just arrived in" (Smith, J, 2003; 19). The artist was Hans, a plumber who wintered at Davis station in 1977. He described the head as "a tribute to patience, winterers, sentinels, waiters, watchers, and direction pointers. It's not ALL rock, ice and machinery, Fred is there too, just because..." (Hans, cited by Smith, J, 2003;19).

Artist Stephen Eastaugh is a present day Antarctic base worker. He has worked as an artist in Antarctica for longer than most in recent times. His is a visual language of wit and whimsy. Using whatever materials are at hand, he makes art works of simple, elemental form. His diptych, Travailogues - M.O.O.P ( Man out of Phase) 200, maps the mind of 'someone disoriented by changing patterns of light and dark in polar regions' (Hince, 2000; 232). Stitched lines through surgical bandage take a line for a walk through an internal landscape.

ANIMATING LANDSCAPE AND HUMAN GESTURE

It is difficult to put into words the genesis and composition of animation. My own experiences and observations of Antarctica, and readings of other people's texts, have suggested some approaches and directions. I am rediscovering ways of working from my past, using some of the dance and movement improvisation techniques that I practised with Hanny Exiner and Al Wunder in the 1980s. One of these techniques is to use key phrases from visual, written or verbal texts, as scores for improvisation. Ideas unfold in a stream of consciousness, with space, time and energy shaped through human movement, and gestural drawing and painting.

There was a turning point on day 35 of my own Antarctic journey, when I felt a new kind of connection between my self and the landscape. On that stormy night at sea, the word "sheet" assumed a dual meaning. Ice sheets tossed by the waves merged in my mind with the bed sheets sliding against my body, which was tossed by the ship's motion.

I felt that the most potent connection I could make with the landscape would be communicated through physical, human movement. If I could not go to Antarctica again myself, then I needed to learn more from the people who had moved through it, to reflect something of this connection through animation.

Texts produced by expeditioners in reponse to their Antarctic experiences, are now being explored for ways to express a kinaesthetic relationship between humans and the Antarctic landscape.

Abstract qualities identified within the aesthetic responses of Elliott and Ward provide scores for animations. Passesges in Ward's 1955 Mawson diary sometimes suggest the Antarctic landscape as a female force. Figure 5 shows the female form that came to mind when I read:

There is silence, but a teasing deceptive untrustable silence and the wind will pump its groan again before there is either stillness or a steady breeze. The sky stays clear or streaked only with bright orange and red bands that against the blue of the ice are like bad make-up.

(Ward, 18 Jan, 1956)

An animated response to 'deceptive untrustable silence' is a puppet unfolding its head in an unexpected ('untrustable'), silent gesture. Its elemental form reflects the starkness of the landscape. Coloured paint will be applied 'like bad make-up' on the face of the Antarctic plateau behind.

Figure 5. Animation, Roberts, 2007

In another diary entry, Ward evokes the inadequacy of human language to describe the scene.

Utterly isolated here, as on another planet. And the silence is accentuated by the scene, and the scene intensifies the silence. You feel estranged. The word lives for the first time, as soon as it is spoken. A long while, almost a horse's whinny comes from the ice and at times strangely like a birdcall.

(Ward, 1955)

The landscape, it seems, is a force in its own right, with its own voice.

ANTARCTIC LANGUAGE

Traveling south, not only does the landscape change, but the meanings of familiar words change. The abstract qualities of Antarctic words can suggest ideas for animation. Bernadette Hince has written a whole Dictionary (Hince, 2000) of words with meanings peculiar to Antarctica. 'Calve', 'sastrugi', 'frazil', 'katabatic' and 'moop' are defined through the writings of people who have responded directly to the landscape. The sound of the word 'moop', reflects its written definition, suggesting a gestures and ways of locomoting through the landscape.

At that latitude it was not clear when day ended and night began, the sun never quite dipping out of sight. Some men fell victim to the unusual phenomenon, becoming "moops", "men-out-of- phase", who slept during the day and emerged at night to wander the decks and lounge in the wardroom totally disoriented.

(1980 (1957) Geo [Aust.] 2(3): 56. cited in Hince, 2000; 232)

The sound of the word 'frazil', and its definition as 'needles or plates of sea ice' (Hince, 2000; 136), inspired Frazil, (Roberts, 2003), in Figure 6. This painting, depicts the fine ice plates that I saw in Antarctica waters, and suggests a way to animate their busy motion on its surface.

Figure 6. Frazil, Roberts, 2003

Antarctica is a landscape of clean lines that can be cut, cracked, torn and stitched. Reflecting on the accumulating written and visual texts of Antarctica, calligraphic marks have been painted and animated on a turning a dress dummy. A frame from a stop-motion, 'straight-ahead' animation sequence can be seen in Figure 7. Improvised lines made on its rotating surface can suggest expeditioner's tracks in the ice, or crevasses, or the motion of snow drift along the surface. The timing can be varied to suggest a slow and plodding traverse, or the dift ice slicing swiftly through the air.

Figure 7. Icelines, Roberts, 2007

DEVELOPING THE ON-LINE WORK

Simon Pockley's on-line work, The Flight of Ducks (Pockley 1995-2007), provides inspiration for interconnecting material collected, and inviting participation. This work, wrote Pockley,

...reflects its content by taking the poetics, conventions, and literary forms of exploration through landscape and applying them to a datascape. The topography of the datascape is shaped by the structural displays of a personal digital repository of texts, images and sounds...these texts are embedded in the datascape as cross referenced hypertexts.

(Pockley, 2005; 1)

The URL: www.antarcticanimation.com is the site of my inquiry. Its interface increasingly reflects Antarctic exploration, with its developing Map, Log and Journey narratives. The content of the site changes over time, reflecting the evolving collection.

A Thesaurus of words, images and animations has been built as part of the site, to reveal different landscape perspectives. Words selected from The Antarctic Dictionary (Hince, 2000) became the first categories for sorting the material. Links to their definitions were also be made. Words such as 'frazil', 'glacier' and 'grease ice' accommodated some of the first material I had to work with. When material relating to places and objects was offered, their names were included. 'Casey', 'Mawson', and 'Kista Dan' are part of the man-made landscape of Antarctica.

Antarctic landscapes represented by expeditioners at different times reflect different aesthetic responses. Different written and visual language features were used to describe Mawson in 1955 than those used by contempoary expeditioers to representat Casey.

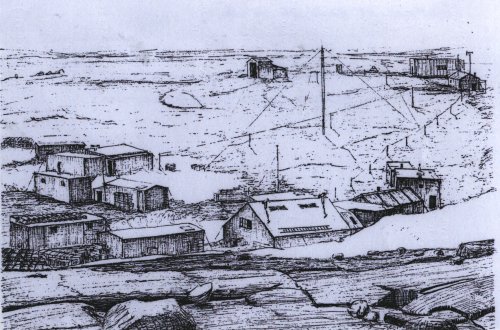

Figure 8. Mawson at end of 1954, Elliott 1956

Elliott's drawing (1956) of Mawson was made from a photograph he took in 1954, when it was first being built. The new buildings are wooden boxes, held down with steel cables into the hard rock. They sit reluctantly, with no relationship to the landscape or with each other. Spaces between the fine, windswept lines suggest the void.

Ward's description of the surrounding desert reflects this feeling.

The space around you seems infinite. This is a place so very new, quite without a human history and it has that clean unlived-in feel of an empty new house.

(Ward, Mawson 1955 diary, 14 March)

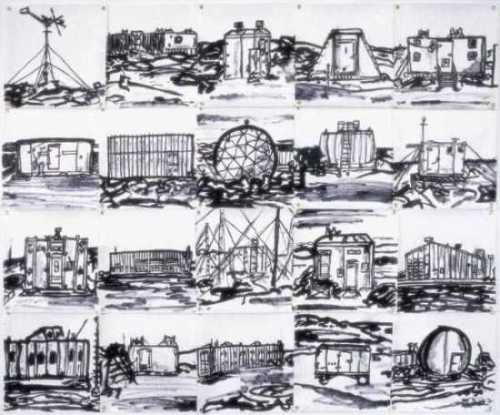

Contemporary representations of Antarctic landscape are provided by Chris Wilson, 2007 Deputy Station Leader for the Australian Antarctic Division at Casey Station in 2007, and artist Stephen Eastaugh. Eastaugh's Casey studies (Figure 9) is a series of ink images drawn on tarp (2000). The title suggests human occupation in pathological terms. Its grid of small images could describe an assortment of alien protuberances growing through skin, or ice. The aesthetic qualities of their work reflect the new materials and technologies (fibreglass and digital respectively) available to them.

Figure 9. Casey studies, Eastaugh 2000

Wilson produced a series of digital time-lapse images of ice moving in Newcomb Bay, with the sky slowly darkening at dusk. His animation reveals an interest in the slow pace of sunset in summer, set against the slightly faster moving ice. Both works reveal an investigative quality. There are many ways being explored to navigate viewers through the on-line work. Words used to describe and explain the landscape are linked with words in The Antarctic Dictionary. The Log, where I reflect on the process of inquiry, has links to other areas of the interface, to maintain connections between composing and analysing material. The Log also invites offers of information and response to work. This function connects the work with the viewer, whose contributions can help to shape the work.

Another way to make connections is through an interactive map. Spatial references can be made to most material in the collection. A latitude and longitude value can be identified for most of the landscape observations and descriptions. This makes makes it possible to have animated journeys intersect spatially, and is an area of great interest, yet to be developed.

As well as accessing scientific data on-line, data is also available from the individuals who have collected and analyzed it. The advantage with this is that they can explain their observations and analyses. As a new member of the Antarctic National Australian Research Expeditions (ANARE) Club, I have met scientists willing to share material: a paleontologist studying fossils of ancient marine life around the Southern Ocean; an archaeologist interpreting Mawson's huts at Commonwealth Bay; a glaciologist researching ice dynamics from Wilkes base; a marine scientist who studied the role of zooplankton poo in absorbing carbon from the atmosphere; a botanist's assistant documenting lichen growth in the Prince Charles Mountains. Scientific data from their research is yet to be explored for its potential for showing changes in the Antarctic landscape through animation. The scientists have agreed to participate in recorded interviews to explain their findings, and to provide visual material where available. They will also describe their aesthetic response to the landscape. Animated sequences of their findings will be integrated with those revealing their various aesthetic responses to the landscape. Finding ways to animate the scientific data is an important part of the research. The purposeful focus of the scientist, it is envisaged, will ground the aesthetic gaze, to engage viewers with the landscape through sense as well as mind.

When embarking on this research, it was not anticipated that personal connections within the Antarctic community would be found. The glaciologist recently met through the ANARE Club was a lodger in my grandmother's house in 1978. Through him and other expeditioners, I have learned that my father relayed messages from his hand-built radio transmitters, between Antarctic bases and Australia in the 1950s and 60s.

It was anticipated that connections would be found between people within the Antarctic community. Some have wintered there up to seven times. Most are linked through roles they have played in advancing Antarctic science. Their stories interconnect, and they identify themselves as a community. Their words have helped to shape an Antarctic dictionary. In life and art and science, it seems that our journeys can interconnect in some small way. Animation can be used to show our different perspectives. An on-line interactive interface can be used to reveal our points of connection, and to invite participation in the dialogue. Animating the shared scientific and aesthetic responses to the landscape of Antarctica can help us understand evidence of the global changes that affect us all.

Bibliography

Boyer, P. 1988, Antarctic journey: three artists in Antarctica, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra

Eastaugh, S. 2000, Casey studies, Series of ink on tarp, William Moira Gallery, Melbourne

URL: http://www.stepheneastaugh.com.au/artworks.htm

[On-line accessed, 2 July 2007]

Eastaugh, S. 2002, Travailogues - M.O.O.P ( Man out of Phase), mixed media, provenance unknown

Eastaugh, S. 2007, on-line dialogue, Antarctic Animation

URL: http://www.antarcticanimation.com/content/thesaurus/m/moop01.php

Elliott, F. 1997, Antarctica in black and white, Portfolio of 24 photolithographs, collections: Mitchell library, Sydney; Australian National Library, Canberra; State Library of Victoria; The Australian Antarctic Division

Fox, W. 2007, Terra Antarctica: Looking into the emptiest continent, Shoemaker & Hoard, San Antonio, Texas

Hans, Man Sculpted by Antarctica, date unknown, permanent collection, Antarctic Sculpture Garden, Davis station, Antarctica

Hince, B. 2000, The Antarctic Dictionary: a complete guide to Antarctic English, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne

Maddock, B. 1993-1998, Terra spiritus: a darker shade of pale, permanent collections: National Gallery of Victoria; Australian National Gallery, Canberra; Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston

Maddock, B. 1987, We live in the meanings we are able to discern, mixed media on 7 panels. On exhibition, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 2007

Pockley, S. 1995-2007, The Flight of Ducks,

URL: http://www.duckdigital.net/FOD/FOD0001.html

[On-line accessed, 12 March 2007]

Pockley, S. Quakes, Quivers and Quacks: how the first ETD (Electronic Theses and Dissertations) has fared over 10 years, ETD 2005 Conference paper, Melbourne, 2005

Roberts, L. 2007, Antarctic Animation,

URL: www.antarcticanimation.com [On-line accessed, 2 July 2007]

Roberts, L. 2003, Frazil, acrylic on canvas, private collection, Sydney

Smith, J. 2003, Fred the head, Aurora - ANARE Club Journal, September 2003, p. 19

Ward, J. 1955, Mawson Diary, Private collection, Melbourne

Wilson, C. 2007, Casey 66O17'S, 110O32'E, digital animation sequence, Newcomb Bay, Casey Station, Antarctica. Private collection, Casey, Antarctica

URL: http://www.antarcticanimation.com/content/thesaurus/c/Casey01.php

[On-line accessed, 2 July 2007]

United States Geological Survey Global Change Research Program website,

URL: http://geochange.er.usgs.gov/data/sea_ice/Derived/images/gif/south/1978/

[On-line accessed, 2 July 2007]

Gulf of Maine Aquarium website,

URL: http://octopus.gma.org/surfing/antarctica/deltaice.html

[On-line accessed, 2 July 2007]

Lisa Roberts

Candidate for PhD, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales

18/06/07