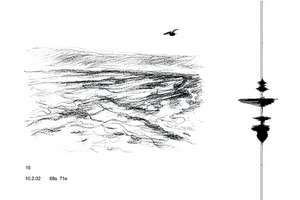

Day 16 /10.02.02 / 68s 71e

animation

Layers of ice,

water,

and wind,

pattern my view.

Preface

The words, pictures and stories of a whalo first inspired me to go to Antarctica. They reminded me how, as a small child, I was told about this place, and how the pictures I was shown and words I had heard used to describe it had fascinated me. But I had never imagined myself there until meeting her. Only when I arrived there did the words of Antarctica even began to have meaning. The landscape had got to work on me, and I began to see my own Antarctica, or at least a small part of it. And there was a sense of isolation in that. I know we all see the world differently, but I was more aware of it in Antarctica than ever before.

My father used to bring seamen to our suburban Melbourne house in the 1950s and 60s, people he had met fixing radios and radar on ships. They came from all over the world. Some were on their way to Antarctica, some were on their way home, or beyond. These huge men would come into my small child world, all from elsewhere, all smelling of the sea. Nobby gave me a book, since lost, with pictures of underwater starfish and zooplankton, his blue eyes fixing on me and on the fragile creatures he identified from his travels. He chattered enthusiastically, his northern English accent alien to my ears. Yet there was a good connection there. Finding that very book recently in the local opp shop kind of confirmed our connection. Jorgan the Swede was more silent, remote, and intriguing in a different way that led me to observe him rather than engage. He spoke with my father about communication technology, and I felt the great distance between ships and land, and people.

When I was at university I lived with my grandmother. One night over dinner, David her lodger discussed glaciology. He was a scientist and used different language. I remember the words 'tongue', 'shelf' and 'crevasse' assuming new meanings. One of the first artists to go to Antarctica with the Australian Antarctic Division was Bea Maddock, my teacher at art school. Sailing towards Hobart on her return, she looked at the coastline of Tasmania through new eyes. This was where she was born, and lived most of her life. Terra spiritus: a darker shade of pale was the major work that followed. In 1995 I had moved to Tasmania and visited Bea in her Launceston studio. She showed me the drawing in progress, explaining the long procees of conceiving and making. Terra spiritus was revealing layers of meaning perceived in the Tasmania landscape by different cultures. Its entire coastline was being mapped and named through cartography (European), contemporary place names typeset in metal plate (English) and by the original Aboriginal place names hand written cursive style using local ochre. Bea said she did this writing best late in the evening, and that drawing the words was like singing. I felt the great sense of distance between Australia's Aboriginal and English heritage, between people now and people then. How would I respond to Antarctica? It was a whalo, a woman living on a small island just off Tasmania, who shared her perceptions of that place, and brought it home to me that I could go and see it for myself.

whalo noun

A whale observer, or 'whale watcher', works as part of a team to document the numbers and behaviours of whales, using stardard systems of observing and recording visual and acoustic data. [LR 2007]

Debra Glasgow, a veteran whalo of the Southern Ocean, was living on Flinders Island in 1999 when we first met. I had been invited to work on the Island as a community artist, animating something of the Island's life with its people: A little skiting on the side. I would fly over there to work, across the small stretch of water between Whitemark and my home in Launceston. From time to time Debra would sail into Hobart from Antartcic expeditions, catch a bus to Launceston and stay overnight with me on her way home. Late evenings watching her slides, only just processed, drew me into her world of sparkling Antarctic seascapes and icescapes. Lights shone in her eyes, and I was curious to see through them, just as I had wanted to see through the eyes of those men I knew as a child. Debra's photographs showed me her world, and I was hooked. I had a strong sense, listening and watching, that she perceived the wildlife and the landscape of Antarctica as one, and that the challenge for humans is to find our place in it, to see ourselves in a landscape indifferent to humans. I had heard that going to Antarctica can be a lifechanging experience, and that scientific studies undertaken there point to climate change. Now I wanted to see what others know of Antarctica, and I dared to see it for myself.