Presentations

Conferences & exhibitions

KRILL LOOKS AND FEELERS:

Expanding perceptions of climate change data

Writer/theatre producer Daniela Giorgiand artist Lisa Robertspresent a theatrical adaptation of the paper co-authored by Lisa and scientist Steve Nicolat the conference Antarctica: Music, Sounds, Cultural Connections,Australian National University, Canberra. Daniela impersonates the scientist. Lisa plays herself.

Theatrical script adapted by Daniela Giorgi and Lisa Roberts from the paper co-authored by Lisa and Steve Nicol:

Krill looks and feelers: a dialogue on expanding perceptions of climate change data pub. The Polar Journal Volume 1, Issue 2, 2011, pages 251-264

Presentation photos: Caroline Huff

Daniela Giorgi (impersonating Steve Nicol) and Lisa Roberts co-presenting at Antarctica: Music, Sounds, Cultural Connections, International conference, Australian National University, Canberra 27 - 29 June 2011

The script is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Copyright license. This means that you can use it for non-commercial purposes as long as you acknowledge the authors Lisa Roberts, Steve Nicol and Daniela Giorgi.

INTRODUCTION (by presenter)

Lisa Roberts (LR) and Daniela Giorgi (DG) are Sydney-based artists. Lisa is an animator and Daniela is a writer, actor and theatre producer. Their presentation dramatises how scientific and artistic methods have been used to make people recognise and care about krill. They bring to life a paper co-authored by Lisa and marine scientist Steve Nicol who propose that recent misconceptions of krill as passive particles are dangerous because they fail to connect people to them as fellow creatures whose well-being is threatened by anthropomorphic changes in our climate. They argue that these misconceptions are being changed, however, by images made by artists and scientists who understand the importance of krill to our well-being and want to communicate that to other people. Lisa and Daniela use animation, dance, images and words to show that krill are not mere drifters in the ocean but that they are purposeful, beautiful, playful and even sexy. Lisa plays herself. Daniela impersonates Steve. The presentation was inspired by two previous presentations in the Antarctic conference series, one by Steve Nicol in Christchurch, 2008 and the other by artist Judit Hersko in Hobart, 2010.

Animation:

Krill watching (with Sophie) from Lisa Roberts on Vimeo.

DG (Approaches lectern and reads from notes):

There is an urgent need to communicate scientific information about climate in order to reach consensus agreement about how we deal with it.

The feedback systems that act between humans and the marine environment are little known outside scientific circles and many of the animals that play critical roles in the oceans are virtually invisible to the general public.

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is one such species and because they are central to the Southern Ocean food web, their well being impacts upon ours. In order to secure the conservation of krill, knowledge of them must reach a wider audience beyond the small number of scientists who study them.

Image: Mary E. White. Earth Alive!

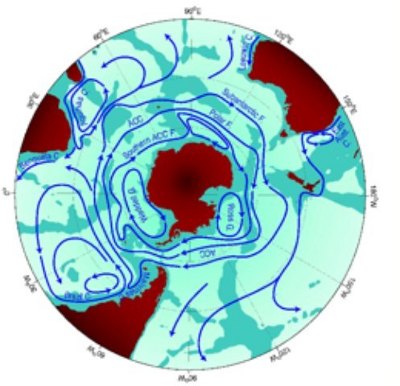

Image: AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). Southern Ocean currents

Image: Uwe Kils. Antarctic krill

DG:

A range of methods of communication are needed because people connect to information in different ways. Scientists and artists need to collaborate in order to more effectively communicate this information to the general public. (pause)

How do we unpack this idea?

DG & assistant from the audience take lid off road case and they move it to the other side of stage

Animation:

A vast scale from Lisa Roberts on Vimeo.

LR (climbs from the road case and then exclaims, while dancing with gestures that echo the animation):

Artists and scientists must collaborate!

DG (turns and says):

What are you doing?

LR (still dancing):

I'm thinking ... (drawing in the air) I'm drawing. I'm drawing a cross to mark the spot of the one solid pivot point of Earth's rotation. And this circle is the circumpolar current that sweeps around Antarctica. This spiralling gesture is how I make sense of what you scientists describe as cold bottom water circulation. When sea ice forms around Antarctica each year cold salty water falls down to the sea floor and is then drawn up and swept around by the circumpolar current.

DG (Unconvinced):

Fascinating

We know that sea ice is an important habitat for krill. It is thought that the algae that grow on the underside of the ice in winter provide a nursery habitat for larval krill and the melting of this massive amount of ice and releasing of the algae into the water in spring, sets off the annual cycle of production in the Southern Ocean. Adult krill feed off the blooms of algae that are left behind by the retreating ice edge and this food supply fuels their reproduction and the cycle continues.

Image: AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). Krill feeding on algae under Antarctic sea ice

LR:

Yes! Krill are key forces that shape the Antarctic environment. And krill have been and continue to be described by artistic and scientific methods. Both ways of knowing are important.

DG (Warming to the idea):

The need to understand how Earth's systems work is urgent because life as we know it is threatened by disruptions in the natural cycles of climate caused by our massive burning of fossil fuels.

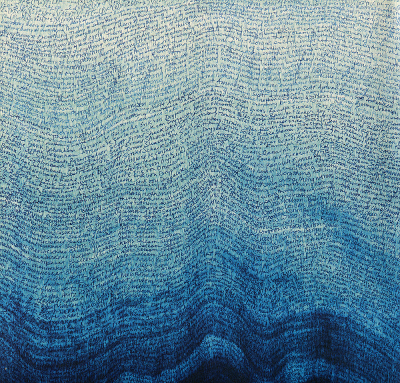

Image: Chris Drury. Explorers at the Edge of the Void (2007)

LR (Pointing to the image):

Deposits of carbon in glacial ice show this global impact. The artist Chris Drury combines artistic and scientific ways of knowing by scribing names between layers of ice recorded on a seismograph.

DG:

Because Earth is more sea than land, it is vital that we study marine life forms in order to understand the global system. However, the marine environment remains largely unknown because few people move through it. This is especially the case with Antarctica, where conditions are notoriously inhospitable to humans. It is easier to make sense of the terrestrial environment that we comfortably inhabit. That krill play a key role in the marine food web, and that our behaviour impacts upon them, is not widely known, and because there is a poor concept of what krill are, few people care.

LR:

But there was a time when krill were known as beautiful creatures. But something happened to change that perception. In earlier times, art and science worked together to make sense of findings in remote uncharted regions. It was common for a scientist to also draw and paint.

The reports of Heroic explorer, Edward Wilson, include an extensive body of art work that has been described as 'a model of lucid recording never surpassed in the annals of polar exploration' (Martin, 1996).

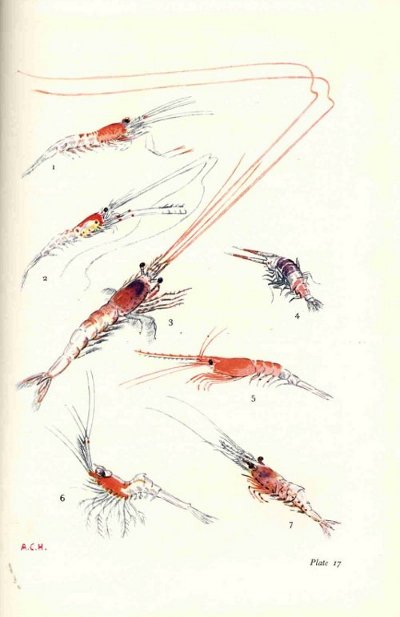

Alister Hardy worked as a scientist and artist in Antarctica in the 1950s. His art expresses his passion and interest in marine biology.

Strong flowing lines in this watercolour of krill describe creatures as at home in the water as we are on land. You can imagine yourself moving with them.

Image: Alister Hardy. Life forms from the open sea

DG:

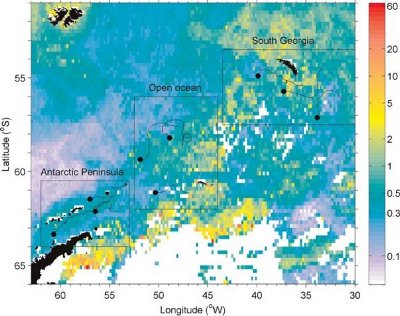

(With authority) Hardy's descriptive methods fell out of favour. New methods of identifying krill, such as satellite imagery, came into use and krill came to be represented as drifting masses of tiny bugs,with computer models displaying their numbers and distribution patterns as myriad dots on screens.

That's how Krill came to be known as plankton, aimlessly drifting inanimate particles in the ocean.

Image: NASA SeaWIFS image krill distribution

Images: AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). Whale feeding on krill (2010)

LR:

Whale food ...

Image: AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). Hardy's CPR deployed

DG:

When in actual fact plankton is anything that is captured by a Continuous Plankton Recorder, or CPR.

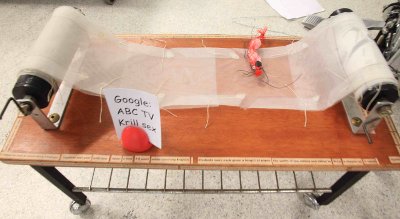

LR (fetching her own CPR and showing it to DG):

And the IRONY is that Alister Hardy invented the CPR!

DG:

This is CPR mesh! Where did you get this?

LR:

I made it. And the krill.

DG:

A CPR captures krill in a mesh, along with many kinds of drifting plants and animals. It is one of the instruments that we use to identify and measure krill mass and is what has led to krill becoming known in terms of their biomass and tonnage. Because we are massive consumers of larger animals in the marine food web within which krill play a key role globally, and because human populations are rapidly growing, it is in our interests to work towards the conservation of krill and their habitats.

The perception of krill as passive homeless drifters is concerning because it deflects attention away from their true nature as living behaving organisms that are in need of conservation.

Image: AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). CPR mesh with krill

LR:

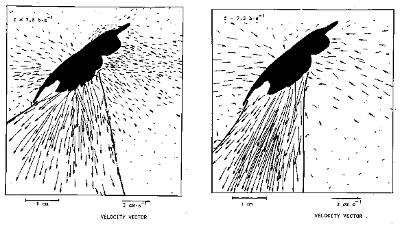

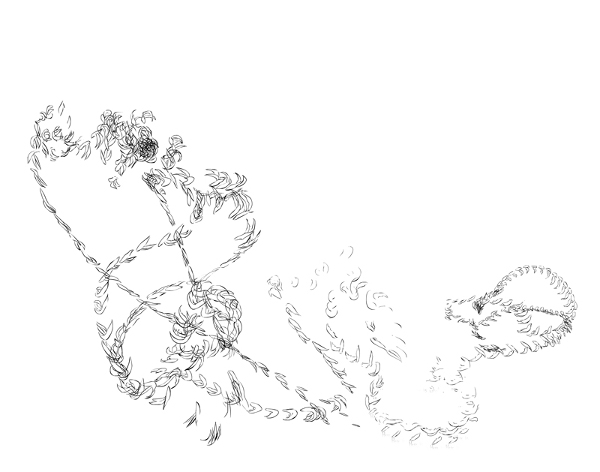

Ah, but there is hope. There are krill biologists who are also artists. This data set by Uwe Kils shows how a single krill stirs up water as it swims.

Imagine this on a massive scale! The flowing lines make visible forces that we know exist but we cannot see. We can connect to the data through our own body memories of swimming. Krill are not passive drifters.

Image: Uwe Kils. Data set of krill swimming actions (1982)

And this painting by Kils shows the beauty of krill through his knowledge of their luminescence.

Image: Uwe Kils. Krill luminescence

Karin Beaumont is an artist who also trained as a scientist. Her work, For the Love of Krill, comes with a notelet that tells us she was 'inspired by microscopic marine life' to 'reveal the beauty & importance of the microscopic world to others, bringing meaning and pleasure to those who wear [it]'.

Image: Karin Beaumont. For the Love of krill

Sensory pleasure can be found in recognising how its form connects to our own human form, (Placing her krill puppet around DG's neck) how the curve of the krill on its string connects to the curve of a neck that wears it.

Sensory, or aesthetic knowledge of forms can connect us to scientific data. At conferences like this, where artists and scientists meet up, collaborations can begin that lead to new methods of research, presentation and publication.

DG:

That's where we've met!

LR:

Yes! In 2008 I heard you present a paper about changing perceptions of krill. Then I followed you to Hobart, to the AAD. You introduced me to the krill nursery where I first drew krill from life.

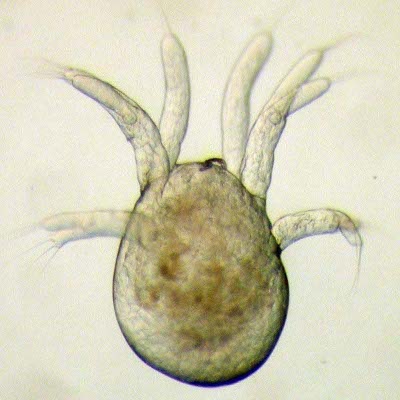

And I saw, through a microscope hooked up to a camera over a petri dish, a baby krill emerging from its egg.

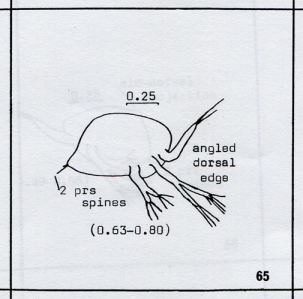

I wanted to know more about this, so I traced a data set by Kirkwood, that describes the stages of normal krill development.

Images: Photos of krill egg hatching

Image: Kirkwood. Data set of normaldevelopment of Euphausia superba (1982)

I asked krill biologist So Kawaguchi to help me make sense of the data, and included words from our dialogue in the animation. Music for the animation was improvised by a 12 year old girl Sophie Green.

Animation:

How krill Grow from Lisa Roberts on Vimeo.

DG:

That's when you found out about krill having sex!

LR:

Yes. I met a woman who was with So Kawaguchi in Antarctica when he saw, through a video camera, krill having sex on the sea floor. She used her hands to describe a crossing, circling and spiralling dance. I had to see that video! So gave me a copy and invited me to help to make some sense of it. At first it was difficult to see what was going on just from looking at the video.

I traced over the video to identify the female and two males that So had seen.

Tracing frame by frame gave me a sense of the action. I found myself co-authoring a scientific paper as an artist. So sent me papers on krill anatomy, and about how shrimp have sex. We exchanged lots of Emails about what we thought was going on.

I found one theory, that krill curl up in a flex position, difficult to believe. I bought prawns from the local fish shop to test it out! And it's possible.

Animation:

Do krill have sex? from Lisa Roberts on Vimeo.

DG:

You know, Lisa, it's only since we've worked out how to breed krill in captivity that we can observe them directly. For the first time, their myriad life stages can be studied. And experiments with live krill can now be done to observe their responses to predicted changes in the marine environment, such as acidification.

LR:

We know how that is going to affect krill.

DG:

If the oceans become as acidic as we predict from current trends, their eggs won't hatch.

LR (drags DG from the lectern to centre stage and moves shoulder to shoulder behind DG and rhythmically recites):

Scientific methods generate consensus understandings about how the world works.

Artistic methods generate individual expressions of sensory connection to the world.

Both ways of knowing are important.

And, when we recognise in both expressions such primal forms as the circle, spiral and cross, we may connect how we think with how we feel.

Enough perhaps to stir us to act in accordance with, not against, what we know are natural cycles of change.

(Facing DG) What do you think?

(Facing audience) What do you think?

Daniela Giorgi and Lisa Roberts rehearse at the Roselle School of Visual Arts, Sydney.