by Eveline Kolijn, 2013

Storyboard for animation by scientist Rob King with artist Lisa Roberts

The early life of krill is about surviving and enjoying the ride.

In summer we spawn in open water.

Our eggs sink and hatch.

Autumn progresses to winter and the ice sheet grows over us.

As baby krill in winter, we are inverted hot air balloonists, flying by night and staying landed in the day.

Through winter we tuck ourselves away in tiny caves under sea ice, grazing away like flocks of sheep, with the sun low in the sky above us, if present at all close to the solstice.

| There are tons of us krill around Antarctica. |

As baby krill we’re in sea ice that’s moved by wind currents.

Exactly at sunset we all herd off the ice like a mass of penguins diving from from the top of an ice flow into the ocean, and swim down into the upper 20 metres of the water beneath.

As soon as we get just below the ice, we’re swept along by water currents.

The ice above continues moving with the wind as we’re carried by water currents beneath, moved in different directions and speeds.

We go where the water current takes us.

We swim up and down OK but can’t compete with horizontal ocean currents.

| For the entire time the sun is down, the pattern of ice flows above us changes with the wind. |

While below in the water we are looping about feeding in our own little world while being driven sideways by the water currents around us.

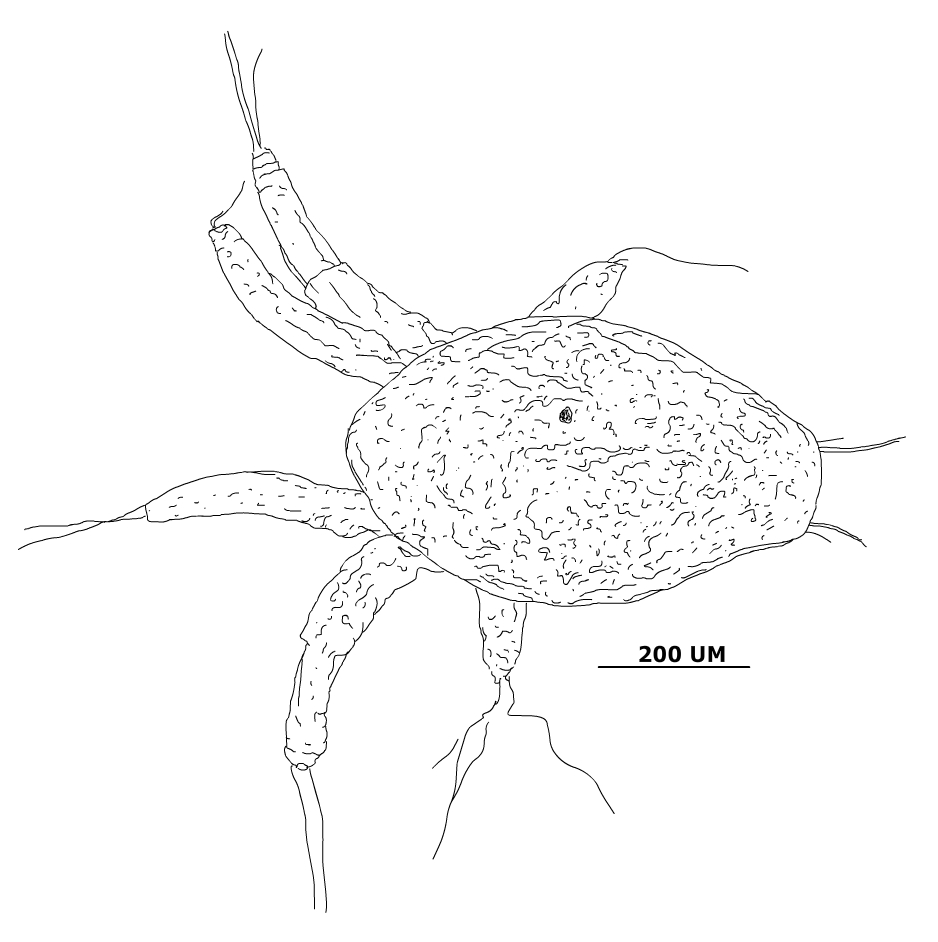

We’re filter-feeding with our front legs and swimming with our hind legs, helpless against water currents but all the time strengthening.

The sun comes up and we charge up to find new ice caves within the pack ice.

Some of us unluckily come up under dead flat sea ice and are eaten by squid or fish or something, while others just next door come up into ice caves that give us some protection.

We begin again to scrape away at the ice like a heard of grazing sheep.

Time flies when you’re busy.

(Accelerate the sequence sort of time lapse style to represent many days and nights. As this is flicking through start to decrease the density of the pack ice to indicate arrival in the MIZ. It will be like this for a long way and then will start to decrease density 9/10th 8/10th etc. all the way to open water which is 6 to 9 months later when the larvae is now bigger and looks pretty much like a juvenile krill at the ice edge munching away on phytoplankton. )

Our growth really takes off when we hit the MIZ, or marginal ice zone, where we find lots to eat.

We dream of the MIZ, a place we have never seen.

The journey to the MIZ is all about just surviving the ride. We’re inverted hot air balloonists, flying by night and staying landed in the ice during the day. Both day and night we hope to move in directions that get us into the MIZ.

As juveniles in open water, our vertical migration behaviour now reverses. As juvenile and adult krill we dive deep during the day (200 metres) to get into darker water for predator avoidance, forming schools also as a predator defense mechanism…

…While below in the water we are looping about feeding in our own little world while being driven sideways by the water currents around us.

Then at night we swim up and disperse to feed on phytoplankton at the surface which is growing strongly from the sun’s energy during the previous day. Then at sunrise we dive down into our schools again.

This is the typical ice free open water behaviour that scientists see for us as juvenile and adult schools of krill.

Rob King:

Date: Wed, 14 Aug 2019 03:45:25 +0000

Rob: “…Ice movement can be the same direction as surface currents but not always. In Bettina [Meyer]’s paper an offset angle between the directions of movement was assumed based on previous papers. If you are trying to relate the story of Bettina’s paper then I would recommend sticking with the concept that the ice and the water underneath are moving independently and are not directly coupled. But I would shy away from portraying this as really different directions, its more likely to be a small offset angle between them. But this is enough to mean that the larvae surface under another piece of ice. Especially if the two trajectories involve different speeds.

The only thing I spotted in your project summary was a typo IPCC rather than IPPC. As to the dates I’m not much help as I don’t deal with this regularly.

Krill have sex from November through to March as far as I know.”